Timber Plantations

Despite the fact that the UK imports about 80% of it's timber, we still grow a lot here on our shores. But what exactly is a timber plantation, how long does it take and what are the key moments?

A timber plantation is an area of woodland, likely some form of conifer, deliberately planted for the purpose of providing timber and timber products at some future point. Where arboriculture is concerned with single trees at a time, the process of growing and managing multiple trees as a woodland is called Silviculture.

In the UK, woodland falls under the scope of the Forestry Commission and they are the folks who produce the data on such matters. They don’t have a metric on how many hectares of plantation land the UK has. But their latest report states that “non-native coniferous woodland is the single largest habitat type in Great Britain, accounting for 1.29 million hectares (42%)”. I don’t think I am being reckless to state that most of that 1.29 million hectares will be used for timber products of some sort. Pulp for paper, fuel for biomass and raw logs for sawmills.

The UK, however, currently only grows 20% of the total timber we consume and the rest is imported. The powers that be are banging the drum to decrease imports in the vein of “timber security” (why does everything have to be secure these days?) so it is likely you’ll start seeing more and more plantations popping up and being felled over the next fifty years.

Before you all conjure up visions of Saruman destroying Isengard and the Forest of Fangorn, let me stop you in your tracks. Most, if not all, gets replanted and eventually it grows back. Maybe not in a nice convenient human time frame so you can feel better about it, but it does grow back. Yes, we lose a bit of habitat, but we also gain a bit of raw material. There are also different silvicultural approaches to choose from and not all of them involve clear felling (removing an entire area in one go) however, I’m not going to cover them, they are outside the scope of this post. Maybe another day.

I’m going to look the timeline of a plantation and the key moments. The purpose is to give the layperson an understanding and (hopefully) respect of the main processes and periods involved in growing timber using the “clear felling” silvicultural approach. It’s also an excuse for me to write something involving time travel. This is not an in-depth guide written by an expert, it is a best effort good faith attempt by me to share my current understanding. If I’ve got anything incorrect – please correct me in the comments.

The present - 2023.

We’re going to be following a fictional geezer called Bob; he was born in 1975. You can see Bob below, he is the handsome fella on the left.

Key moment 1: Planting

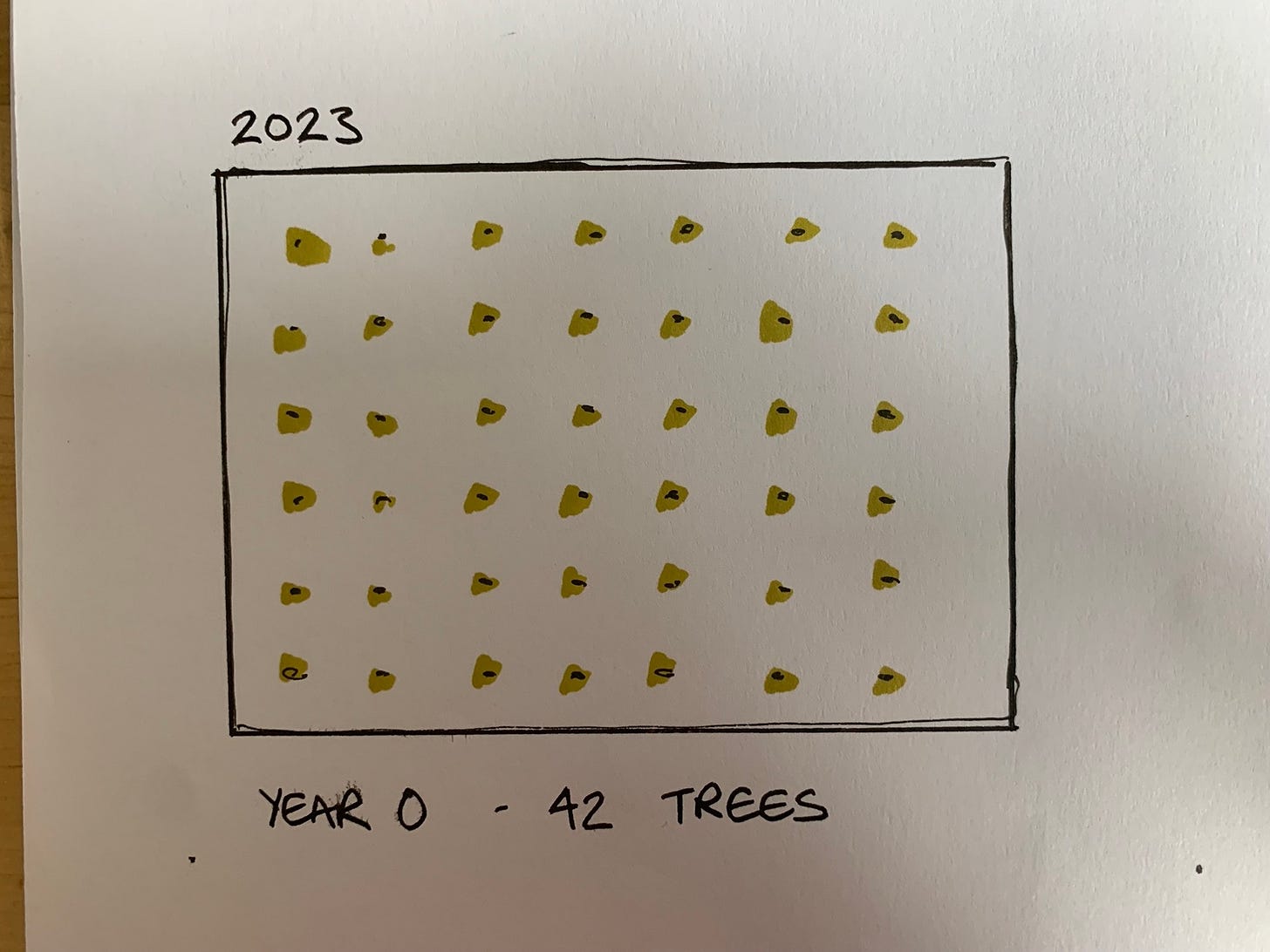

Bob planted everything at just the right time of year and he is also going to be the one managing the plantation day to day and also appearing in all of our pictures. Bob has planted a fictional softwood species called Arboriculum coniplantata in a ridiculously small 16 metre by 14 metre area (0.024 hectares) plot.

Bob planted his trees at 2 metre spacings, so in total he has 42 trees. This arial view really does show how small the 16 × 14 metre site is. Fortunately for us, it makes drawing it very easy. If you’re wondering why you’d place the trees so close together, that shall become apparent in the future.

Now that Bob has planted his trees we can call this year zero. There’s not much more for him to do this year aside from ensuring that deers, rabbits, grey squirrels, voles or any other pest or disease affects these trees. Bob is a keen shot and carries all the correct licenses to shoot any non-desirable invertebrate.

Key moment 2: Beating up

There’s a process called “beating up” which Bob will have to do one year in the future. Beating up simply means replacing all of the trees that have died in their first year. As Bob has planted the Arboriculum coniplantata species, none will die as it is very hardy species and makes this best case scenario easy to write about.

Ok, all aboard the time machine. Let’s scoot forward a decade.

🚀

2033 - Year 10

Welcome to the future. I cannot tell you anything about it as I don’t want to break the space time continuum.

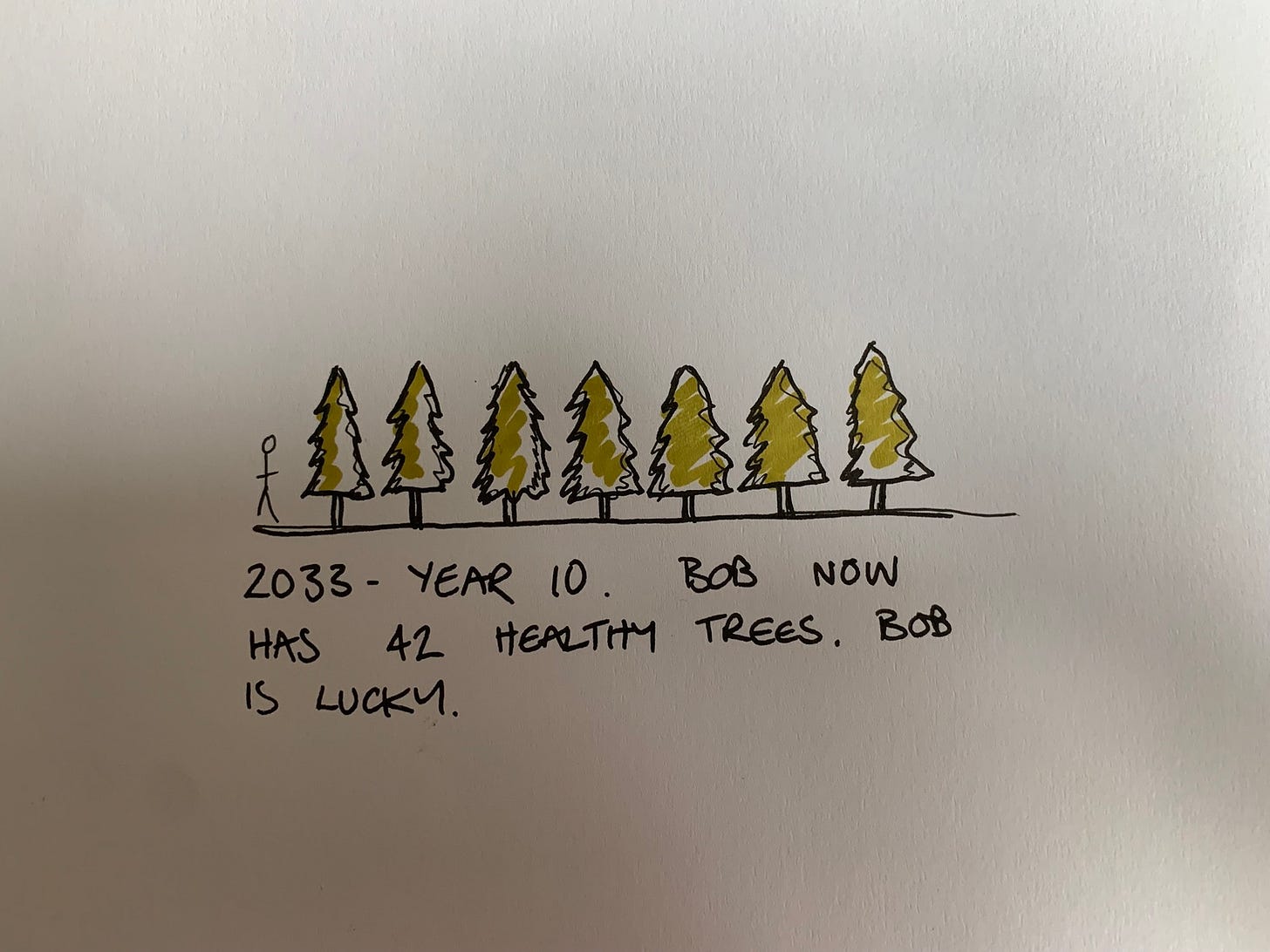

It has been ten years since Bob planted his trees and as you can see, Bob has been keeping himself in shape. The trees are all healthy and starting to look a little more like trees.

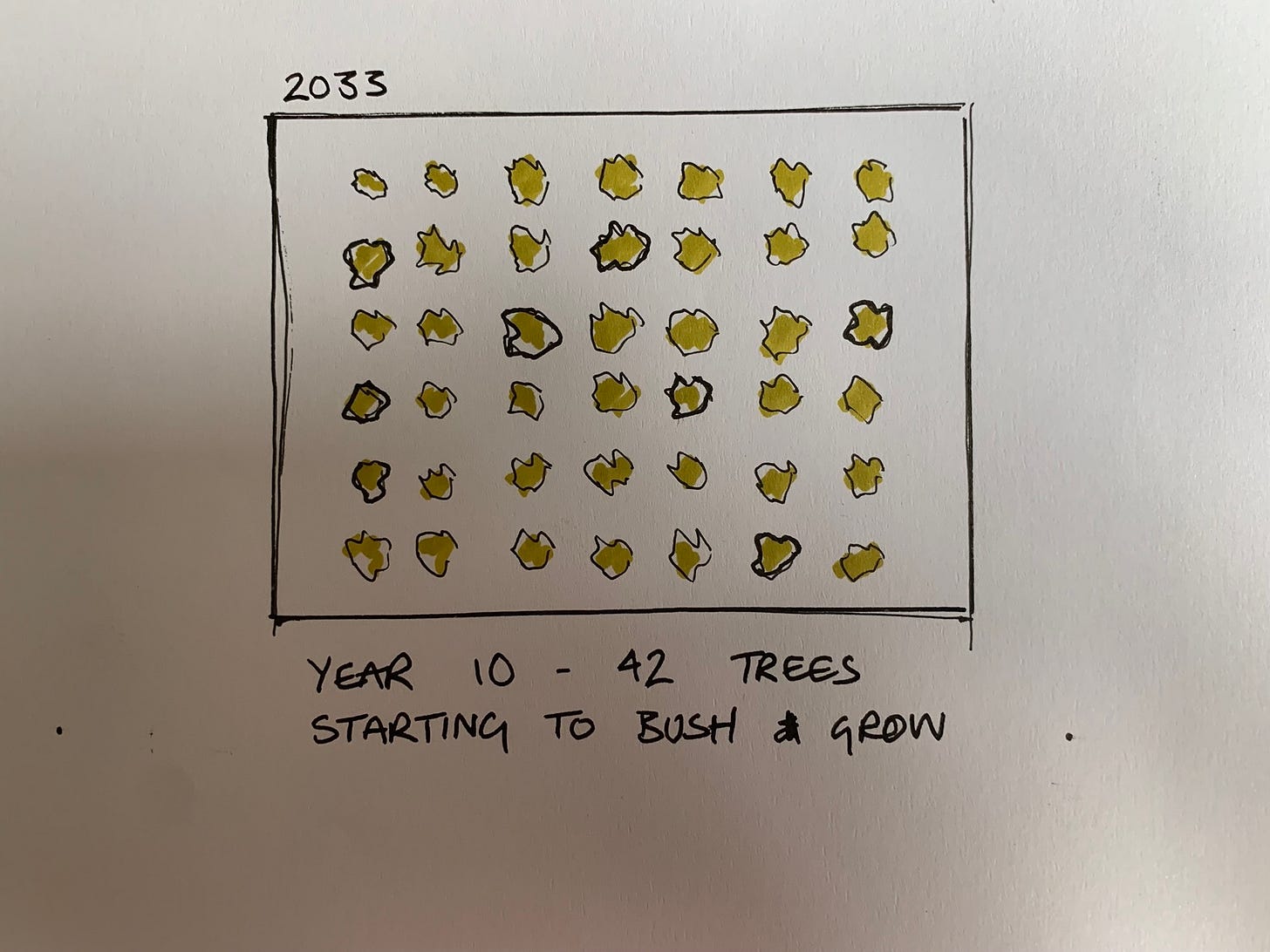

Bob has done a great job of keeping his plantation free of pests and diseases and he’s really beginning to see the benefits of doing so. If we take an arial view we can see how the trees are starting to bush out. It won’t be long before they are all beginning to touch each other.

If you remember back to 2023 when Bob planted the woodland, he planted everything in 2 metre spacings. This was done in order to force the trees to grow straight. The way it works is quite clever. Trees left to their own devices will do crazy things and grow in all kinds of weird and wonderful shapes. These trees are no use for the timber industry as typically, timber is straight. By planting the trees close together, as soon as they begin to touch each other they understand that in order to compete, they have to grow straight up - and quickly.

Here’s a screen grab from a Google Maps of a plantation in Northumberland before the site was clear felled (meaning everything is felled) in 2019. It was re-planted by myself and three others in 2022/23. These were big trees, some of the stumps were in excess of three feet. Note how they are all tightly packed together. This is one way to grow straight timber. In just the section you see here, we planted at least 1000 trees.

Back to Bobs plantation though and it is all looking good. Here’s hoping it looks like the above in fifty years.

Let’s hop in the time machine once again and scoot forward five years this time.

🚀

2035 - Year 15

Bob is still working hard. He would have been enjoying retirement soon as he is sixty three, but in 2034 the conservative government raised the retirement age to 85. Luckily Bob loves his job and for a 63 year old, he’s in great shape.

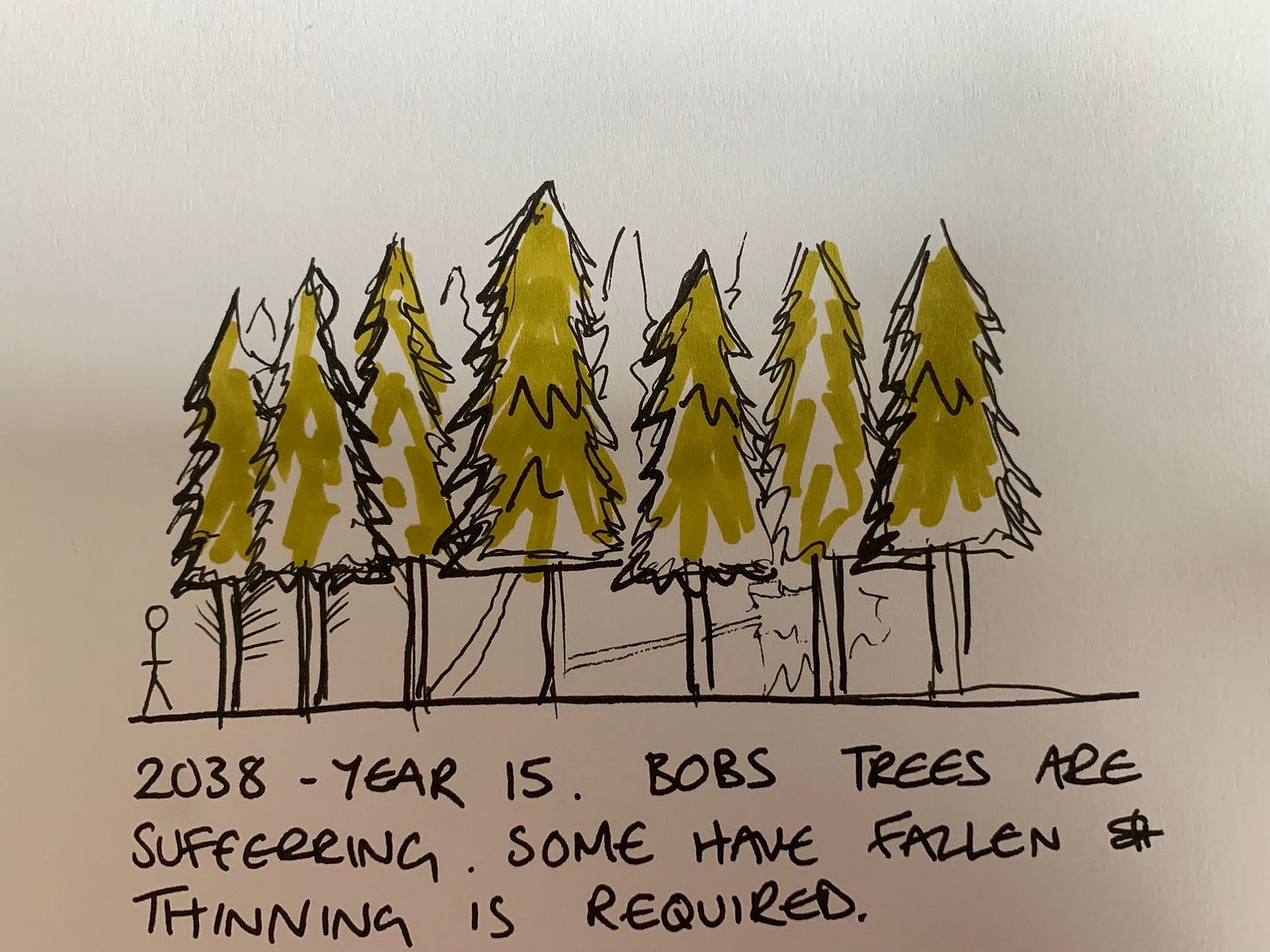

However the last five years have been a mixed bag for his plantation. On the plus side, Bob now has a woodland. Just look at it! The trees have now created a full canopy that totally covers the floor. Of course, this isn’t ideal woodland habitat (because monoculture) for native flora and fauna, but I’m not getting into that here. Instead, let us be excited for Bob’s great job. 15 years ago this was a field and now it is a woodland!

All is not well though. In not so good news, there have been a few storms that have blown over a few of the weaker trees. These are shown in the image above. Consequently, a few of the trees have started to deviate from growing straight and have started to grow in a bendy shape to access the space in the canopy left by those falling trees. You can see a bendy stem a few rows in.

Also, as a result of the full canopy some lower limbs of some trees stop receiving light a few years ago and have started to die. This isn’t much in the grand scheme of things now, but it does mean that some trees will be getting stronger and some will be getting weaker. You can see this in the arial view.

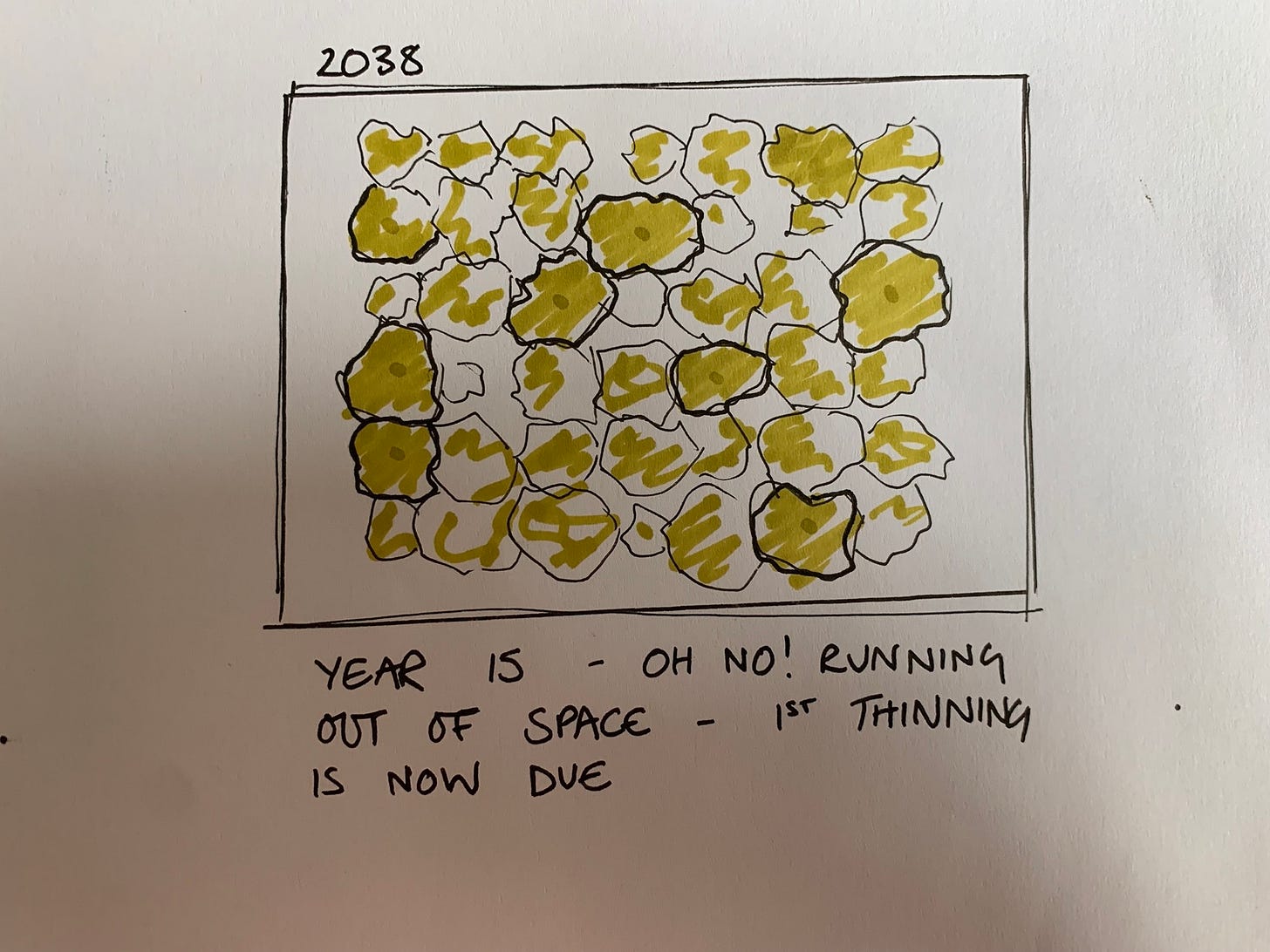

Key moment 3: First thinning

Bob has decided It is time for the first thinning. At last, we can let our chainsaws roar!

Thinning is the process of removing the low quality and weaker trees. Typically a woodland may be thinned twice or more before the final harvest (many years in the future). My felling experience at treeschool has been in doing the first thinning. Practically every tree you fell gets hung up (gets stuck in branches and then you spend a chunk of time expending a load of energy getting it SAFELY onto the ground).

When doing a thinning job, each site will have a certain specification for how much to thin, what to do with the resulting timber and what to do with the arisings (limbs and foliage). At treeschool we were thinning 1 in 3 trees. This means for every three trees, remove one. Sometimes it can be 1 in 4. The right ratio depends on a number of factors such as the age of the trees, their condition and what the management objectives of the woodland are. Bob’s woodland is tiny and purely fictional so he’s going to remove 1 in 2.

In terms of what to do with the timber, in the treeschool City & Guilds exam I had in March 2023 (still await results - suspect passed), the specification was to cut the timber into two metre lengths and stack it no higher than one metre in height. At my recent NPTC felling exam (I passed - yay) which was also a thinning job, the spec was two foot lengths.

What happens with the timber depends on who owns it. Typically, first thinning may be sold on as firewood, biomass or pulp. Trees selected for thinning are not really suitable for sawmills because either the diameter of the stuff is too small to turn into dimensional timber or the wood is not straight enough. This is evidenced below where you can see one of my classmates processing a tree that is about eight inches in diameter. You can also see a stack of thicker stuff that was selected because it wasn’t straight.

Back to Bob’s woodland plantation. He’s going to be thinning 50% of it, which is way too aggressive for a real world plantation, but as this woodland is an example, it’s fine and helps keep the maths nice and simple. Bob will be doing the thinning - he may be in his sixties but he is firmly in the “use it or lose it” camp. Good for Bob. Everyone should be more like Bob.

Once again unto the time machine. This time thirteen years into the future.

🚀

2048 - Year 25

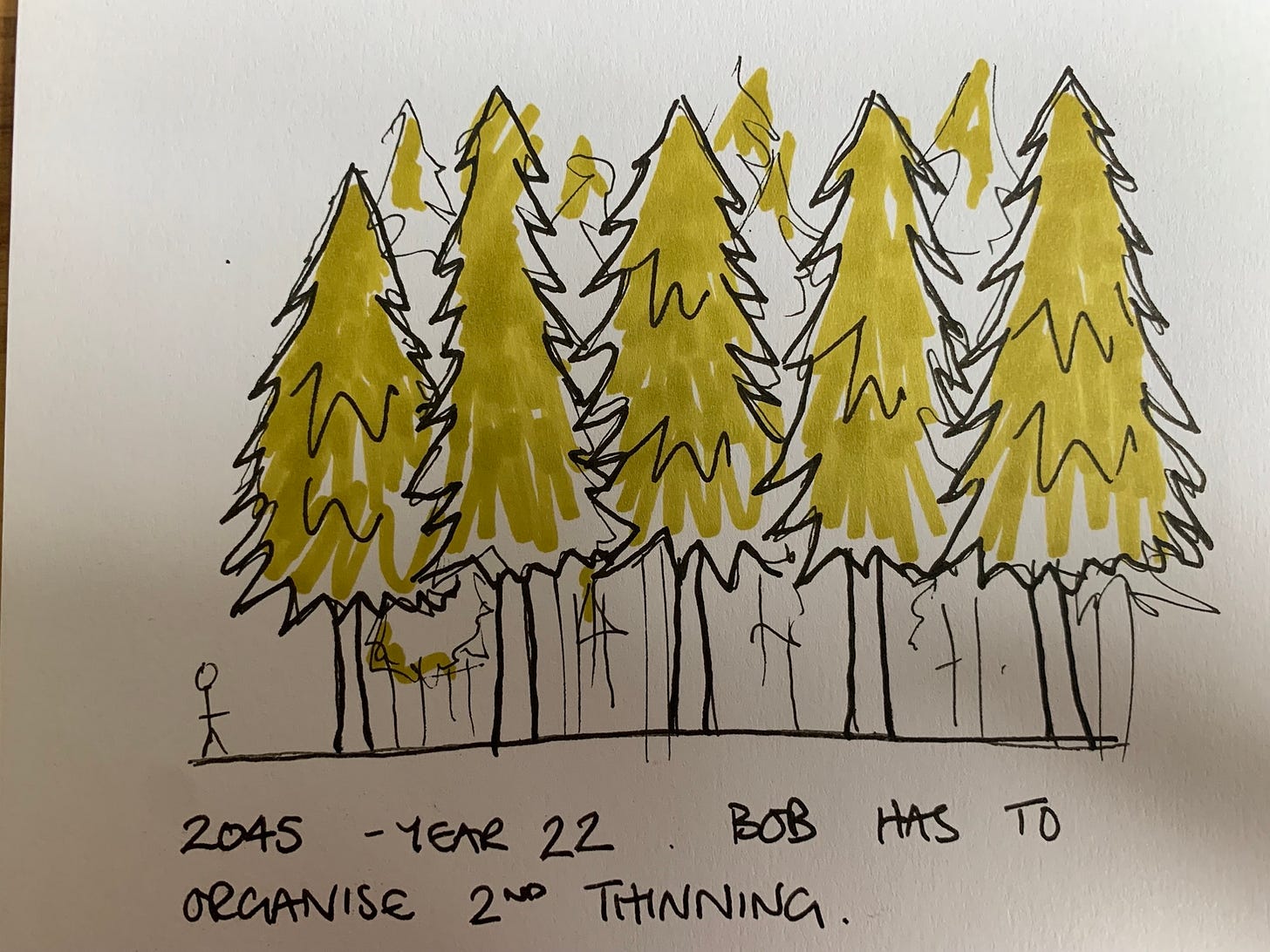

It has been nearly quarter of a century since Bob planted his woodland. Bob is now 78 and he’d be due to retire in seven years, but the Labour government raised the pension age to 96. Don’t ask - it’s a touchy subject for Bob. Anyway, it has been seven years since the last thinning and these trees have shot up (carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere are not all bad) and now require a second thinning.

Key moment 4: Second Thinning

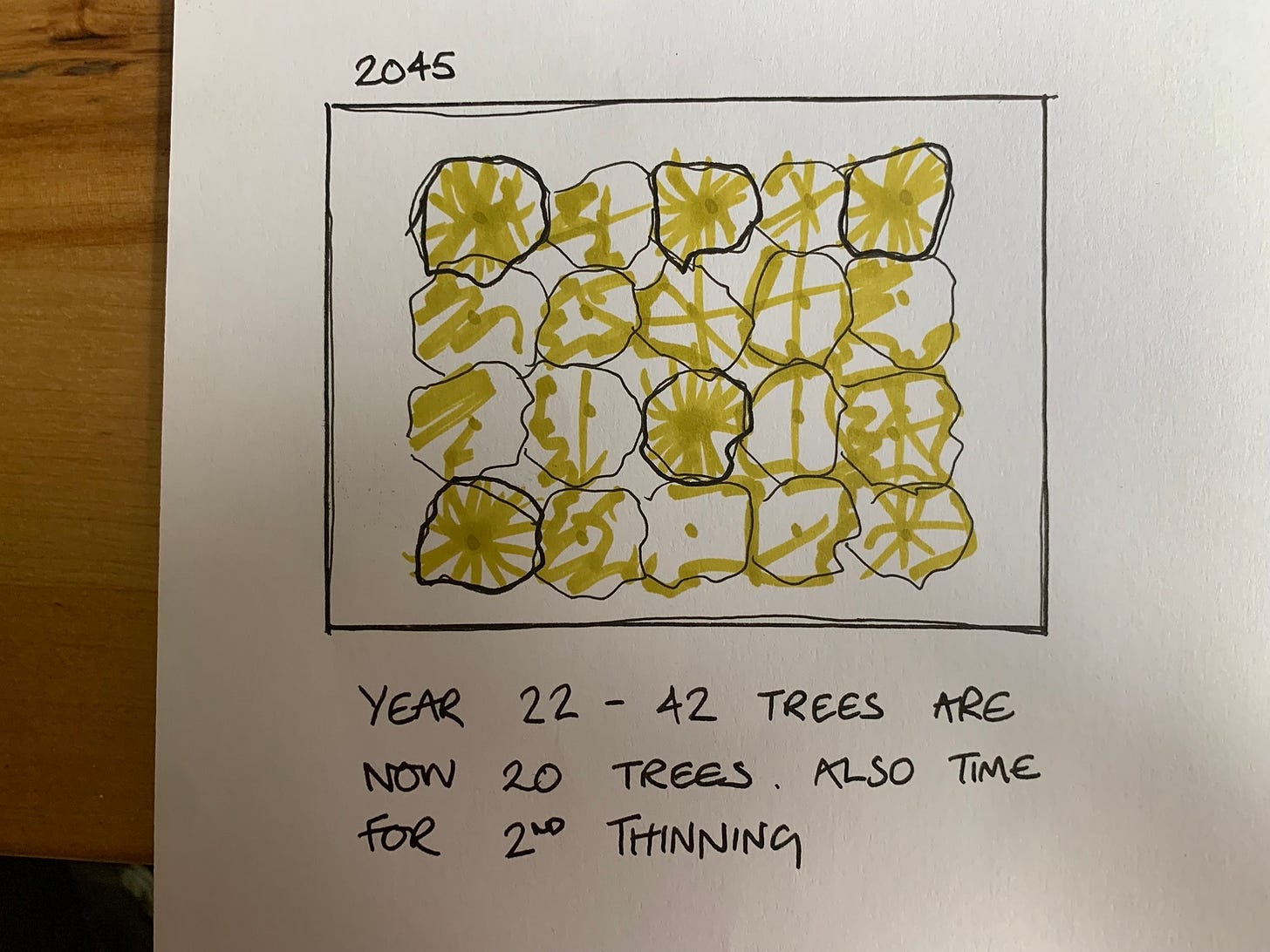

Even though Bobs woodland started off with 42 trees, he now has 20. Thinning is not an exact science and so you don’t always precisely hit the target. None the less Bob now has 50% less trees than he did before and now he has to thin them again! The trees just won’t stop growin’.

The lower quality timber from this thinning will be going into the pallet industry and the higher quality stuff will be going to the sawmill. The pallet route is common for second thinning stuff. This is now you can sometimes stumble onto some nice wood in pallets. lf you’re buying a thing that comes from a part of the world that also does a lot of hardwood exporting, you can expect to find many fine (but short, probably oily and full of holes) lengths of wood in pallets from this region.

The reason it is time for the second thinning is that the trees have not yet reached their sizes and once again, they are butting up against one another. You can see this in the arial view below.

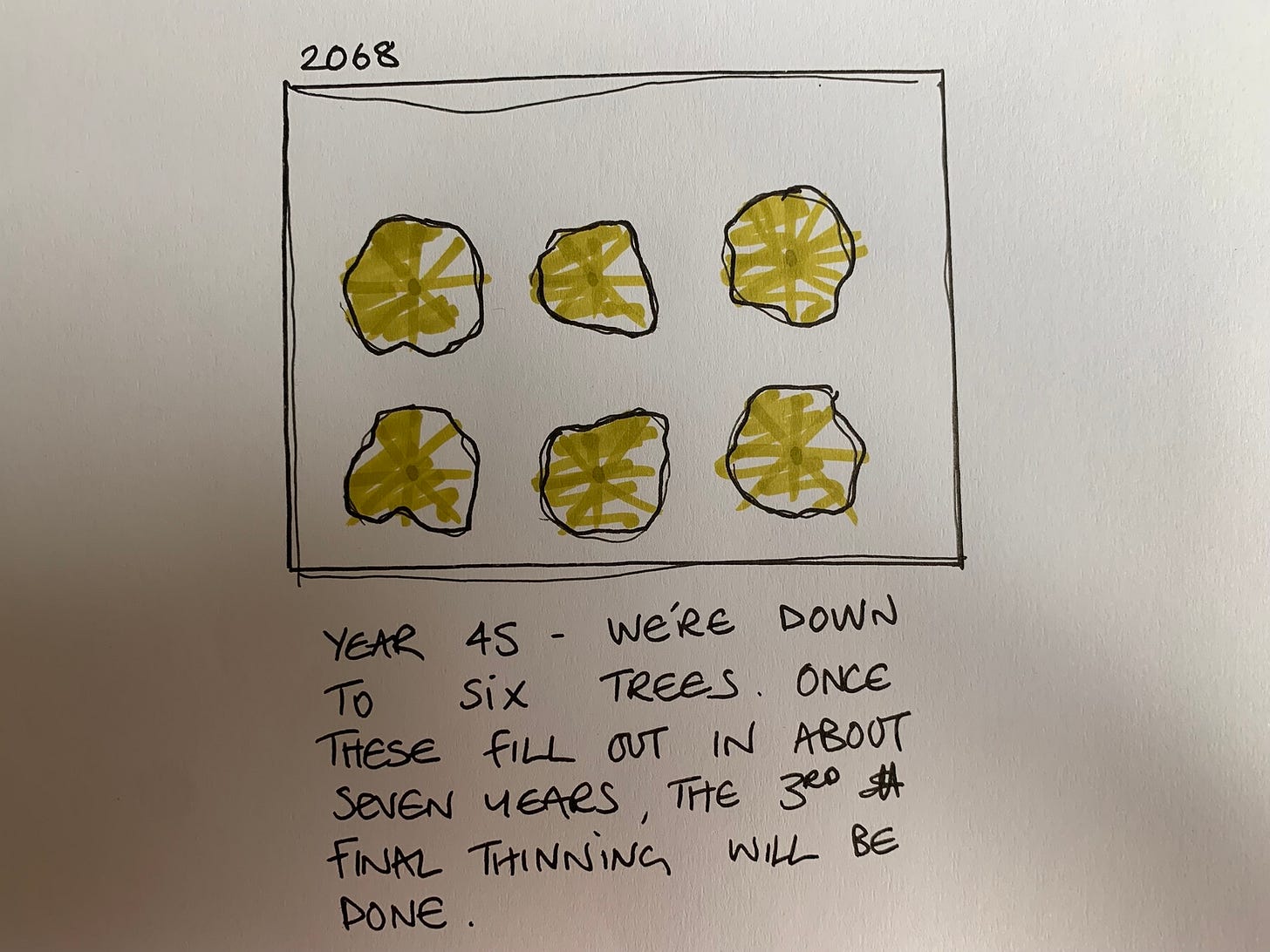

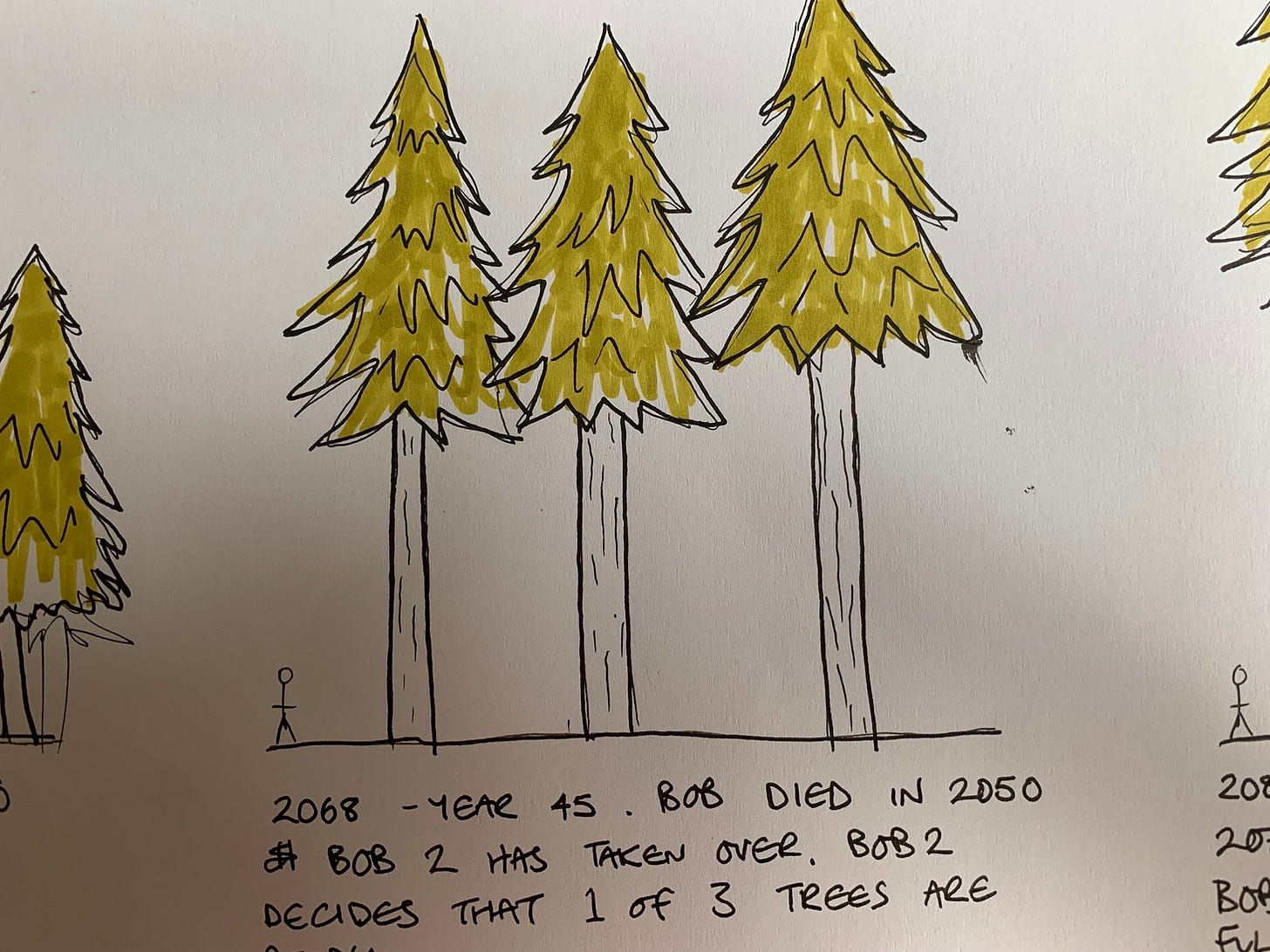

2068 - Year 45

Firstly, it is with great sorrow that I have to tell you that Bob passed away in 2050. He died at the young age of 93 and he was in spitting distance of retirement and his pension. Bob 2 (his replacement) is below.

The idea of Bob dying and being replaced may seem like somewhat of a joke but there is a point to be made. Much of woodland work spans generations. By the time the woodland I planted at in 2022 in Northumberland will be ready for harvest at some point in 2080, I will be over one hundred years old and odds are - quite dead. Think about that for a moment. Not many industries have stark reminders of your mortality like this. Did you start a project at work this week that won’t complete until so far in the future that you’ll be dead?

Back to Bob 2. The second thinning resulted in the woodland being cut back rather aggressively into just six trees. In 2023, Bob started off with forty two trees and now in 2068 we are down to six.

It is a good job Bob was not managing a real woodland as this would have been far too aggressive. I suspect Bob thinned this much to make it easier for me to draw and talk about.

Key moment 5: Third Thinning

Bob 2 is now considering a final thinning of one in three trees. Nearly all the trees on site are approaching maturity and by removing 33% of them now, the remaining stock will pack on a huge amount of girth which will significantly increase their weight and thus, their value.

It may seem crazy to take out more trees when there are so few already, but giving the other two the space and resource to grow as much as they can will give significant increases on the log sizes when they are finally harvested. The Timberland Investor has a great video on this topic.

The time machine has two more trips in it, let us embark for our penultimate journey fifteen years into the future.

🚀

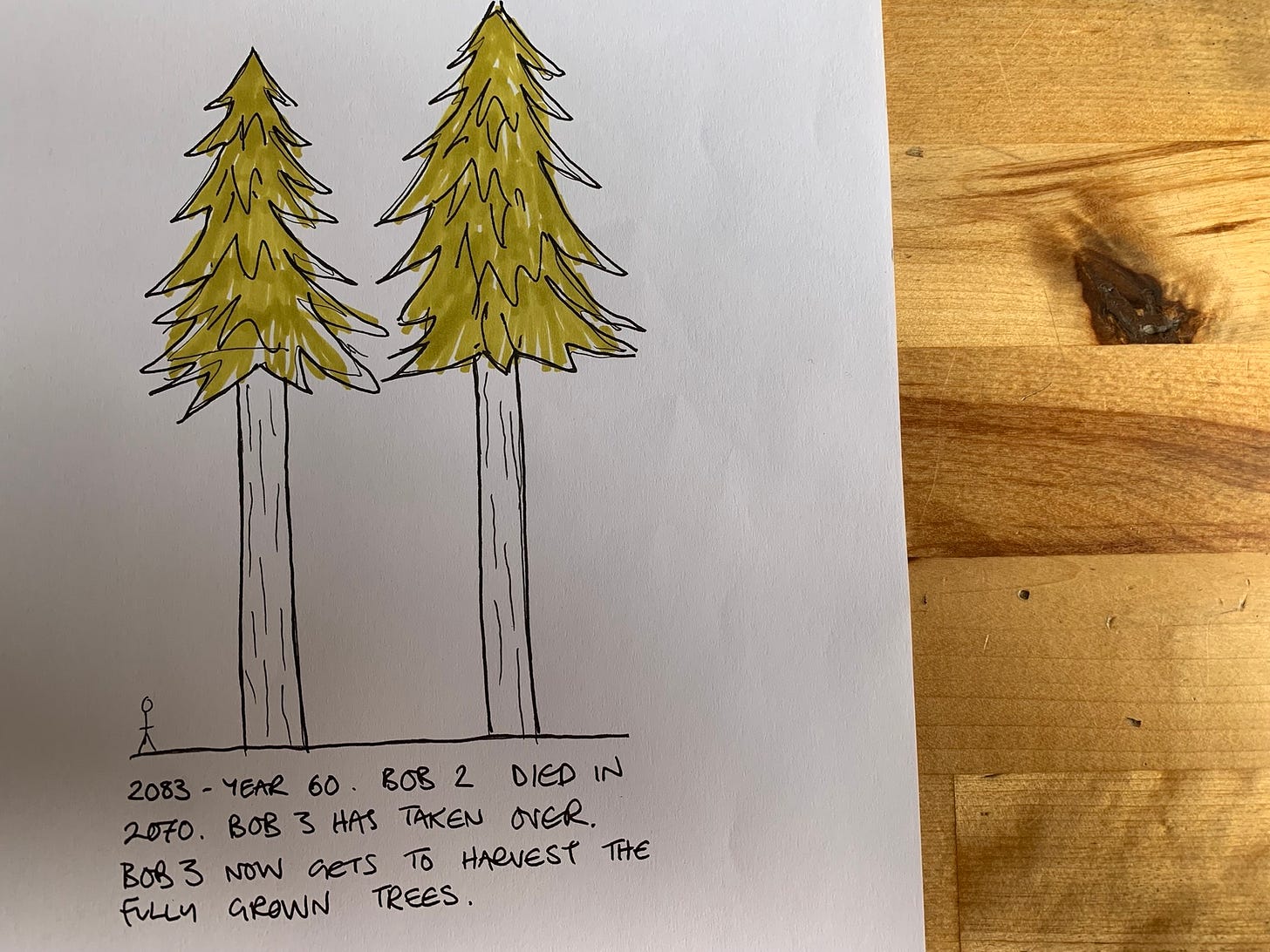

2083 - Year 60

Bad news first, Bob 2 died in 2070 at the age of 68. His vintage hydrogen cell car developed a leak in the fuel tank and exploded. He was warned about this, but Bob 2 would not be told and he always did what he wanted. Classic Bob 2.

Bob 3 is now the guy in charge of the woodland. This woodland has now spanned three generations of woodsmen.

Key moment 6: Final Harvest

What was once a field of 42 saplings in 2023 is now a stand of four mature Arboriculum coniplantata ready for harvesting in 2083.

Behold the magnificent, straight, thick, textbook trees that three generations of Bobs have managed to produce. These are perfect logs for the sawmill.

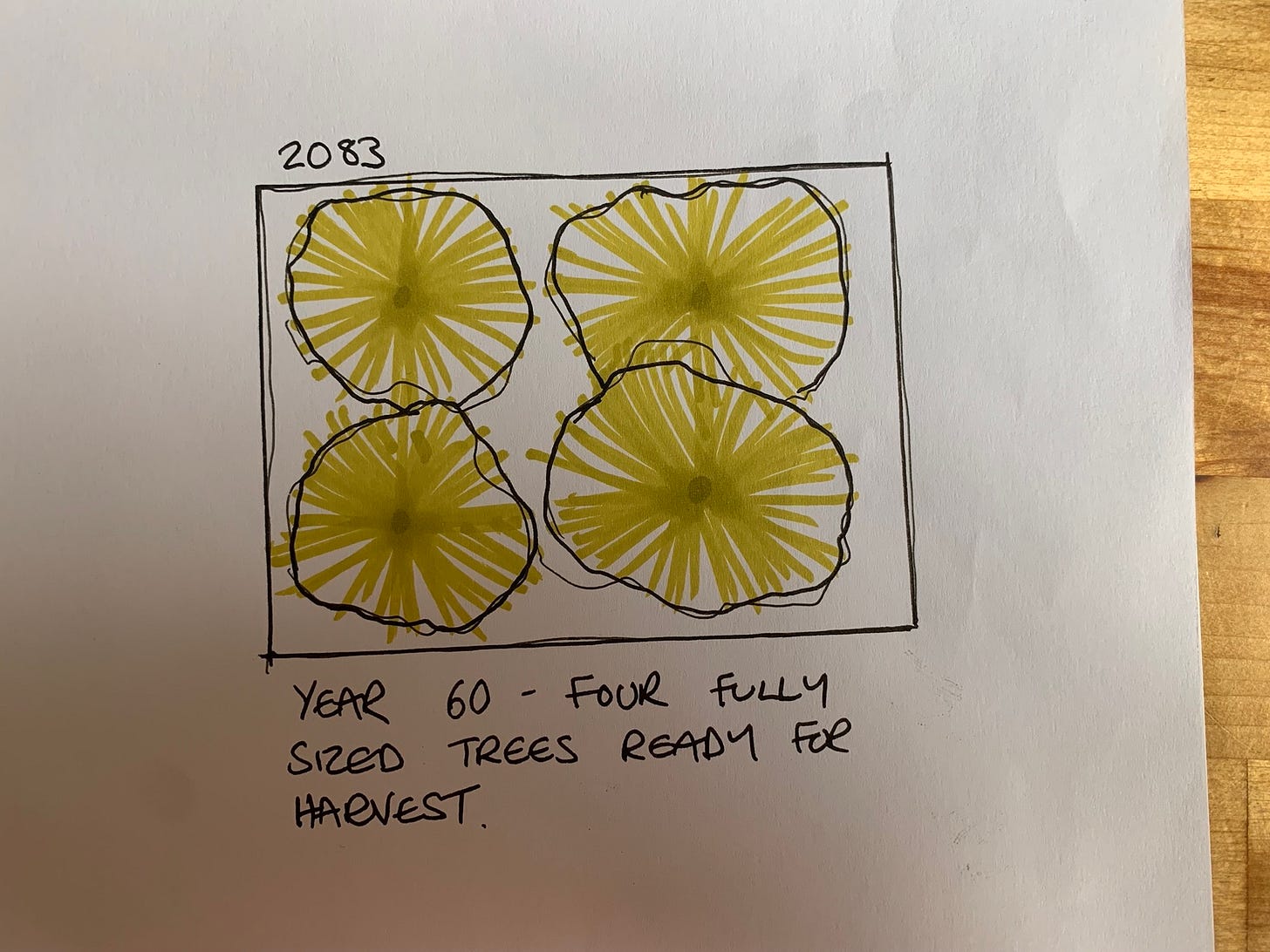

If we take a look from above, we can see that their crowns have developed into a near complete canopy covering the woodland.

Obviously, once these trees are felled the ground will be just as it was in 2023 and ready for planting again. Maybe Bob 3 will start the cycle again so that Bob 6 gets to harvest more trees in 2143? In truth, no one knows what will happen. The past and future are always ideas.

We need to get back into the time machine so I can wrap this thing up.

We return to the present.

🚀

The Present

This was a whistle stop tour of a typical plantation in the UK and a mildly odd experiment in time travel for me. I wanted to show the main events in a timber plantation are planting, beating-up, thinning and then, finally, the harvest. I also wanted to give some kind of graphical representation to show the changes in the total amounts of trees and canopy coverage of the plantation as the trees were thinned to the final harvest. I’ve missed out a lot of topics, some of which are critical to the way we manage our timber stocks in the UK. This omission has been deliberate as I wanted to just focus on key moments in a typical plantation.

To give you an idea of the complexity here’s a brief mention of all the issues that come to mind. Each of these are suitable candidate for large stand alone essays. There’s the issue of non-native mono crops and how they affect local ecology, their fragility to disease. There’s predicting what species will excel and thrive in a climate that no-one can predict in fifty or more years. There’s protection from pests and diseases and the costs involved in the on-going management. There’s the local residents, visitors and aggressively vocal activists who probably object to your plans. There’s the infrastructure required to extract your harvest and the necessary planning permission to create tracks and roads. Let’s finish with the hard task of knowing when to harvest your timber. Getting the right price is critical and whilst your thinning may be based on the physical condition of the plantation, it also has an economical aspect. If demand for pulp and chips is sufficiently strong, you may wish to fell more of the young growth to realise a profit today. Of course, this means you lose sawmill logs in the future, but that’s an issue for Bob 3, not you. This is all a very long winded way of saying “it’s not only complex, but worse than that, it is complicated”.

Wrapping up

Designing, managing and ultimately harvesting a timber plantation is a complicated business riddled with traps and unexpected disasters. It is not for the feint of heart and every time you drive past a stand of conifers or any woodland for that matter, it would be a suitable response to experience awe. The odds were always stacked against that stand existing and yet there it is. It’s probably older than you are, likely older than your parents and maybe even your grandparents.

As complex and old as the plantation is though, in the clear felling silviculture approach there are only a small number of key moments - planting, thinning and harvesting. As a newbie in treeschool it has been eye opening to be a part of the planting and thinning processes. It’s given me a respect not only for the process, but also for the timelines.

For the third and final time I’ll ask the question - how often is it that you start a project at work that you know will never finish until well after your death? Below is a photo I took whilst on work experience at an estate in Northumberland. In the tree planting harness you can see fresh sitka and Norway spruce ready to be planted. They won’t be ready until at least 2080 and I will probably be dead then. The tree planting harness sits on a harvested sitka spruce stump that was about four feet in diameter. It was apparently 85 years old when it was harvested in 2018. This means is was planted before the second world war.

In this one photo we see a process that started in 1930 that won’t complete until 2080.

One hundred and fifty years is a lot of Bobs.

Wow Jamie, you taking us to tree school with you…don’t really need all the technical stuff just the fun bits…